common name: South American fruit fly (suggested common name)

scientific name: Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) (Insecta: Diptera: Tephritidae)

Introduction - Synonymy - Distribution - Description - Hosts - Economic Importance - Management - Acknowledgements - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) is an insect pest commonly referred to as the South American fruit fly, which occurs from Southern USA to Argentina (Figure 1). Recent research has revealed this species to be a complex of at least eight cryptic species (yet unnamed), currently described as morphotypes, rather than a single biological species (Hernández-Ortiz et al. 2004, 2012, 2015).

Figure 1. Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) female laying eggs in a peach. Photograph by Dori Nava, Embrapa Clima Temperado.

Overall, the morphotypes in the Anastrepha fraterculus complex are highly polyphagous with the potential to infest at least 110 host plants, including economically important fruit crops, such as guava, citrus, and apples (Zucchi 2016). However, depending on their distribution, each fly morphotype may have its own host range, which is still unknown. Uncertainties around the taxonomic status of the Anastrepha fraterculus complex represent a huge challenge to plant protection authorities (Hendrichs et al. 2015). Because of the economic importance of this group of flies, it is crucial to know which species within the complex are indeed insect pests in order for plant protection authorities to establish quarantine barriers and prevent the introduction of pest species across countries and spread within each country.

Synonymy (Back to Top)

The suspicion that Anastrepha fraterculus was a complex of multiple species was initially raised by Stone in 1942. Subsequently, the status of cryptic species within Anastrepha fraterculus was confirmed by multiple lines of evidences, such as isozymes (enzymes with different amino acid sequences that catalyze the same reactions), karyotypes, molecular cytogenetics, morphometry, chemical profiles, and behavioral studies (Morgante et al. 1980, Steck 1991, Selivon and Perondini 1998, Smith-Caldas et al. 2001, Hernández-Ortiz et al. 2004, 2012, 2015, Selivon et al. 2005, Canal et al. 2015, Vera et al. 2006, Cáceres et al. 2009, Rull et al. 2013, Devescovi et al. 2014, Vanicková et al. 2015, Dias et al. 2016). These cryptic species of the Anastrepha fraterlus complex are often called morphotypes, representing groups of similar organisms.

Currently, eight morphotypes are recognized in the Neotropics as part of the nominal species Anastrepha fraterculus: Andean, Brazilian-1, Brazilian-2, Brazilian-3, Ecuadorian, Mexican, Peruvian, and Venezuelan morphotypes (Hernández-Ortiz et al. 2004, 2012, 2015). Those eight morphotypes are related to three distinct and directly unrelated phenotypic lineages, Andean, Brazilian, and Meso-Caribbean, suggesting the non-monophyly of the Anastrepha fraterculus complex Hernández-Ortiz et al. 2015). However, to date, all phenotypes from the Anastrepha fraterculus complex remain named Anastrepha fraterculus.

The following synonyms for Anastrepha fraterculusare listed by the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS 2017):

Dacus fraterculus Wiedemann, 1830 (original designation)

Tephritis mellea Walker, 1837

Trypeta unicolor Loew, 1862

Anthomyia frutalis Weyenbergh, 1874

Anastrepha peruviana Townsend, 1913

Anastrepha braziliensis Greene, 1934

Anastrepha costarukmanii Capoor, 1954

Anastrepha scholae Capoor, 1955

Anastrepha pseudofraterculus Capoor, 1955

Anastrepha lambayecae Korytkowski & Ojeda, 1968

Distribution (Back to Top)

Species of the Anastrepha fraterculus complex are native to and most common in South America (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela), but can also be found in Central America (Guatemala, Panama) and North America (Mexico and the USA).

Description (Back to Top)

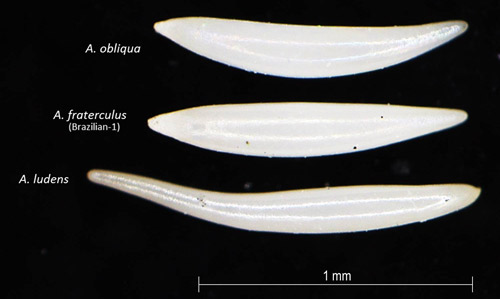

Eggs: In general, the Anastrepha fraterculus eggs are creamy white, elongate, averaging 1.35 mm to 1.42 mm, have a conspicuous micropyle (opening for sperm entry) as well as a short chorionic extension in the egg apex, and are bluntly rounded in the egg end (Figure 2) (Murillo and Jirón 1994, Selivon and Perondini 1998). Eggs from different morphotypes within the Anastrepha fraterculus complex may differ regarding length, position of the micropyle, structure of papilla, pattern of sculpturing of the chorion, size, and number of aeropyles (respiratory channels) (Selivon et al. 1997, Selivon and Perondini 1998). Females deposit eggs into the fruit through sclerotized ovipositors. The eggs hatch into larvae within two days.

Figure 2. Egg morphology of Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann), Brazilian-1, in comparison to other Anastrepha species. Photograph by Vanessa Dias, University of Florida.

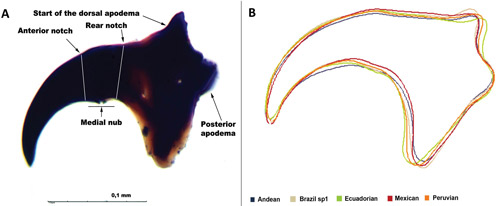

Larvae: In order for Anastrepha fraterculus larvae to reach maturity, they must molt three times. Usually, the first instar occurs from 1 to 3 days old, the second instar from 4 to 6 days old, the third instar (Figure 3) from 7 to 12 days old (Nieuwenhove and Ovruski 2011). The average body length of the third instar ranges from 8.77 mm to 10.02 mm across morphotypes (Canal et al. 2015). Several larval traits can be used to identify the different morphotypes within the Anastrepha fraterculus complex, particularly mandible shape, as shown in Figure 4 (Canal et al. 2015).

Figure 3. Ventral (top) and lateral (bottom) views of the Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) (Brazilian-1) third instar larvae. Photograph by Vanessa Dias, University of Florida.

Figure 4. (A) Mouth hook of third instar larva from lateral view. (B) Estimated morphological differences in the shape of mouth hook of five morphotypes of the Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) complex. Photograph by Canal et al. (2015), ZooKeys, open access under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

Pupae: The pupal stage is inert, but extremely important due to the intensive level of cellular differentiation. Pupae of the Anastrepha fraterculus complex are cylindrical and brownish, becoming darker when the insect is fully developed (Figure 5A), but still inside of the pupae as a pharate adult (Figure 5B). In nature, pupae usually can be found buried in the ground. Pupae hatch into adults within two to three weeks.

Figure 5. Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) pupae. (A) Pupae of different ages (note change in coloration as pupae age – older one in the left). (B) Puparium with a pharate adult (fully formed fly) inside. Photograph by Vanessa Dias, University of Florida.

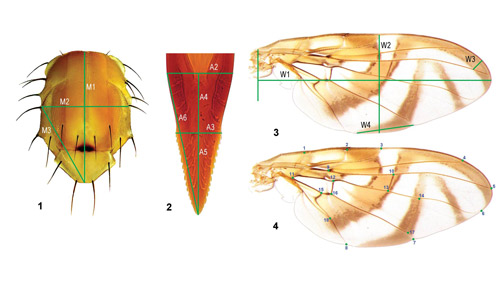

Adults: The adults in the Anastrepha fraterculus complex are colorful, usually yellowish brown, ranging from 12 to 14 mm. Although they are highly variable, aspects of wings, genitalia (particularly female genitalia), and thorax (mesonotum) constitute important characters to identify the species within the complex (Hernández-Ortiz et al. 2004, 2012, 2015) (Figure 6). According to Greene (1934), Anastrepha fraterculus adults can be distinguished from other species of the genus by the shape of the ovipositor (females) and wing pattern. There is no sexual dimorphism, except in the sexual characters and size (females are usually larger than males) (Figure 7). For instance, one of the characteristics exclusive to females is the ovipositor that can measure 2 mm long.

Figure 6. Morphological characters used to identify individuals from the Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) complex. 1. Thorax. 2. Aculeus tip (part of the ovipositor). 3 and 4. Multiple measurements from the wings. Photograph by Hernández-Ortiz et al. (2015), ZooKeys, open access under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

Figure 7. Female (left) and male (right) of Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann). Both specimens are from the Brazilian-1 morphotype. Photograph by Vanessa Dias, University of Florida.

Sexual behavior of these insects is complex, variable, and very interesting. Males from the Anastrepha fraterculus complex exhibit a lek mating system in which calling individuals get together on trees (usually under the leaves) to attract, court, and mate with receptive females (Morgante et al. 1983) (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) mating. Photograph by Vanessa Dias, University of Florida.

Multiple signals, such as visual (symmetry of structures), acoustical (buzzing) and chemical (pheromones), are used by males to court females (Segura et al. 2007, Gomez-Cendra et al. 2011, Brizová et al. 2013, Dias et al. 2016) (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Male from the Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) complex releasing pheromone to attract females (see the abdomen tip of the male). Photograph by Vanessa Dias, University of Florida.

Hosts (Back to Top)

The species within the Anastrepha fraterculus complex infest at least 110 host plants including several families, such as Anacardiaceae, Annonaceae, Myrtaceae and many others (Zucchi 2016):

| Anacardium occidentale, cashew | Mangifera indica, mango |

| Andira humilis | Manilkara zapota, sapodilla |

| Annona crassiflora, araticum do cerrado | Marlierea edulis |

| Annona rugulosa, custard apple | Mouriri acutiflora |

| Averrhoa carambola, starfruit | Mouriri glazioviana |

| Butia eriospatha, wooly jelly palm | Myrceugenia euosma |

| Byrsonima, serrettes | Myrcia aff. clausseniana |

| Campomanesia spp., guavira, white guabiroba | Myrciaria cauliflora, Brazilian grapetree |

| Carica papaya, papaya | Myrciaria jaboticaba, Brazilian grapetree |

| Celtis iguanaea, Iguana hackberry | Passiflora edulis, passion fruit |

| Chrysophyllum gonocarpum, white star apple | Picramnia sp., bitterbush |

| Cydonia oblonga, common quince | Plinia glomerata, yellow jaboticaba |

| Citrus aurantifolia, key lime | Plinia strigipes |

| Citrus aurantium, bitter orange | Pouteria caimito, abiu |

| Citrus limon, lemon | Pouteria gardneriana, abuai |

| Citrus maxima, pomelo, jabong | Pouteria ramiflora |

| Citrus reticulata, tangerine | Prunus avium, wild cherry, sweet cherry, gean |

| Citrus sinensis, orange or sweet orange | Prunus domestica, plum |

| Coffea arabica, common coffee | Prunus mume, Chinese plum, Japanese apricot |

| Coffea canephora, robusta coffee | Prunus persica, peach |

| Cryptocarya aschersoniana | Prunus sellowii, wild Brazilian peach |

| Diatenopteryx sorbifolia | Prunus sp., peach |

| Diospyros kaki, Japanese persimmon, kaki | Psidium araca, wild guava, Brazilian guava |

| Eriobotrya japonica, loquat | Psidium cattleyanum, strawberry guava |

| Eugenia brasiliensis, Brazil cherry | Psidium guajava, guava |

| Eugenia dodoneifolia | Psidium guineense, Brazilian guava, Castilian guava, sour guava, Guinea guava |

| Eugenia gemminiflora | Psidium kennedyanum |

| Eugenia involucrata, cherry of the Rio Grande | Psidium myrtoides, araçá-una |

| Eugenia leitonii, araçá piranga | Psidium sellowiana |

| Eugenia platyphylla | Punica granatum, pomegranate |

| Eugenia platysema | Pyrus communis, European pear |

| Eugenia pyriformis, uvaia | Rollinia aff. sericea |

| Eugenia schomburgkii | Rollinia emarginata |

| Eugenia stipitata, araçá, araçá-boi | Rollinia laurifolia |

| Eugenia uniflora, Surinam cherry | Rollinia sericea, araticum-alvadio |

| Ficus carica, fig | Rubus sp., raspberries, blackberries, dewberries |

| Fortunella japonica, round kumquat | Rubus ulmifolius, Elmleaf blackberry |

| Fragaria ananassa, strawberry | Salacia campestris |

| Fragaria vesca, strawberry | Simaba guianensis |

| Garcinia brasiliensis, bakupari | Solanum sp. |

| Helicostylis sp. | Spondias dulcis, ambarella, jew plum |

| Inga edulis, ice cream bean, monkey tail | Spondias purpurea, jocote |

| Inga sellowiana, ingá mirim, ingá da serra | Spondias sp., hog plums, Spanish plums |

| Jacaratia heptaphylla | Stenocalyx dysentericus, cagaita, cagaiteira |

| Jambosia sp., rose apple | Syzygium aqueum, watery rose apple |

| Malpighia emarginata, Barbados cherry | Syzygium jambos, rose apple |

| Malpighia glabra, Barbados cherry | Syzygium malaccense, Malay rose apple |

| Malpighia sp., cherries | Terminalia catappa, Indian almond |

| Malus domestica, apple | Vitis vinifera, grapes |

| Ximenia americana, tallow-wood |

Economic Importance (Back to Top)

Anastrepha fraterculus is an important pest in South America. For instance, attack by females from the Brazilian-1 morphotype to apple orchards in Southern Brazil can result in economic losses estimated at U$S 110 million (about 5% of the production or approximately 60,000 tons). In the same region, it is estimated that the losses in peaches can reach around 40% of the total production. Grapes can also be attacked, but the larvae cannot complete their development (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Damage to grapes caused by females of Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) complex. Photograph by Vanessa Dias, University of Florida.

Management (Back to Top)

Besides pesticides and toxic baits, more environmental friendly techniques can be applied to reduce the population of insects from the Anastrepha fraterculus complex. One of those approaches is the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT), a method of control based on the reduction of fertility in a target population through the mating between sterile males (released males from the laboratory) and fertile females (wild females from the target pest population) (Lance and McInnis 2005).

The successful implementation of SIT programs depends on correctly understanding species boundaries within the Anastrepha fraterculus complex because sexual compatibility is a requirement for the success of the technique (Hendrichs et al. 2015). In addition, biological control and mating disruption are other promising strategies that can be used in integrated pest management programs to control Anastrepha fraterculus populations.

Acknowledgements (Back to Top)

The authors would like to thank Vicente Hernández-Ortiz, Instituto de Ecología AC - Mexico, Nelson Canal,Universidad del Tolima - Colombia, and Silvana Caravantes, International Atomic Energy Agency, for reviewing this article and contributing with helpful suggestions.

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Břízová R, Mendonca AL, Vanickova L, Silva CED, Tomcala A, Paranhos BAJ, Dias VS, Joachim-Bravo IS, Hoskovec M, Kalinova B, Nascimento RRD, da Silva CE, do Nascimento RR. 2013. Pheromone analyses of the Anastrepha fraterculus (Diptera: Tephritidae) cryptic species complex. Florida Entomologist 96: 1107-1115.

- Cáceres C, Segura DF, Vera MT, Wornoayporn V, Cladera JL, Teal P, Sapountzis P, Bourtzis K, Zacharopoulou A, Robinson AS. 2009. Incipient speciation revealed in Anastrepha fraterculus (Diptera: Tephritidae) by studies on mating compatibility, sex pheromones, hybridization, and cytology. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 97: 152-165.

- Canal NA, Hernández-Ortiz V, Tigrero SJO, Selivon D. 2015. Morphometric study of third-instar larvae from five morphotypes of the Anastrepha fraterculus cryptic species complex (Diptera, Tephritidae). In De Meyer M, Clarke AR, Vera MT, Hendrichs J (Eds) Resolution of Cryptic Species Complexes of Tephritid Pests to Enhance SIT Application and Facilitate International Trade. ZooKeys 540: 41-59.

- Devescovi F, Abraham S, Roriz AKP, Nolazco N, Castaneda R, Tadeo E, Cáceres C, Segura DF, Teresa Vera M, Joachim-Bravo IS, Canal N, Rull J. 2014. Ongoing speciation within the Anastrepha fraterculus cryptic species complex: The case of the Andean morphotype. Entomologia Experimentalis Et Applicata 152: 238-247.

- Dias VS, Silva JG, Lima KM, Petitinga CSCD, Hernández-Ortiz V, Laumann RA, Paranhos BJ, Uramoto K, Zucchi RA, Joaquim-Bravo IS. 2016. An integrative multidisciplinary approach to understanding cryptic divergence in Brazilian species of the Anastrepha fraterculus complex (Diptera: Tephritidae). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 117: 725-746.

- Greene CT. 1934. A revision of the genus Anastrepha based on a study of the wings and on the length of the ovipositor sheath (Diptera: Trypetidae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 36: 127-179.

- Hendrichs J, Vera MT, De Meyer M, Clarke AR. 2015. Resolving cryptic species complexes of major tephritid pests. In De Meyer M, Clarke AR, Vera MT, Hendrichs J (Eds) Resolution of Cryptic Species Complexes of Tephritid Pests to Enhance SIT Application and Facilitate International Trade. ZooKeys 540: 5-39.

- Hernández-Ortiz V, Bartolucci AF, Morales-Valles P, Frias D, Selivon D. 2012. Cryptic species of the Anastrepha fraterculus Complex (Diptera: Tephritidae): A multivariate approach for the recognition of South American morphotypes. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 105: 305-318.

- Hernández-Ortiz V, Canal NA, Tigrero Salas JO, Ruíz-Hurtado FM, Dzul-Cauich JF. 2015. Taxonomy and phenotypic relationships of the Anastrepha fraterculus complex in the Mesoamerican and Pacific Neotropical dominions (Diptera, Tephritidae). In De Meyer M, Clarke AR, Vera MT, Hendrichs J (Eds) Resolution of Cryptic Species Complexes of Tephritid Pests to Enhance SIT Application and Facilitate International Trade. ZooKeys 540: 95-124.

- Hernández-Ortiz V, Gomez-Anaya JA, Sanchez A, McPheron BA, Aluja M. 2004. Morphometric analysis of Mexican and South American populations of the Anastrepha fraterculus complex (Diptera: Tephritidae) and recognition of a distinct Mexican morphotype. Bulletin of Entomological Research 94: 487-499.

- Lance D, McInnis D. 2005. Biological basis of the sterile insect technique. In Dyck VA, Hendrichs J, Robinson A. (eds) Sterile Insect Technique: principles and practice in area-wide integrated pest management. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 69-94.

- Morgante JS, Malavasi A, Bush GL. 1980. Biochemical systematics and evolutionary relationships of Neotropical Anastrepha. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 73: 622-630.

- Murillo T, Jiron LF. 1994. Egg morphology of Anastrepha obliqua and some comparative aspects with eggs of Anastrepha fraterculus (Diptera, Tephritidae). Florida Entomologist 77: 342-348.

- Nieuwenhove GAV, Ovruski SM. 2011. Influence of Anastrepha fraterculus (Diptera: Tephritidae) larval instars on the production of Diachasmimorpha longicaudata (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) progeny and their sex ratio. Florida Entomologist 94: 863-868.

- Rull J, Abraham S, Kovaleski A, Segura DF, Mendoza M, Clara Liendo M, Teresa Vera M. 2013. Evolution of pre-zygotic and post-zygotic barriers to gene flow among three cryptic species within the Anastrepha fraterculus complex. Entomologia Experimentalis Et Applicata 148: 213-222.

- Selivon D, Morgante JS, Perondini ALP. 1997. Egg size, yolk mass extrusion and hatching behavior in two cryptic species of Anastrepha fraterculus (Wiedemann) (Diptera, Tephritidae). Brazilian Journal of Genetics 20: 587-594.

- Selivon D, Perondini ALP, Morgante JS. 2005. A genetic-morphological characterization of two cryptic species of the Anastrepha fraterculus complex (Diptera: Tephritidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 98: 367-381.

- Selivon D, Perondini ALP. 1998. Eggshell morphology in two cryptic species of the Anastrepha fraterculus complex (Diptera: Tephritidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 91: 473-478.

- Smith-Caldas MRB, McPheron BA, Silva JG, Zucchi RA. 2001. Phylogenetic relationships among species of the fraterculus group (Anastrepha: Diptera: Tephritidae) inferred from DNA sequences of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I. Neotropical Entomology 30: 565-573.

- Steck GJ. 1991. Biochemical systematics and population genetic-structure of Anastrepha fraterculus and related species (Diptera: Tephritidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 84: 10-28.

- Stone A. 1942. The fruit flies of the genus Anastrepha. U.S. Department of Agriculture Miscellaneous Publication 439: 1-112. Washington, D.C.

- Vaníčková L, Břízová R, Pompeiano A, Ferreira LL, de Aquino NC, Tavares RF, Rodriguez LD, Mendonça AL, Canal NA, do Nascimento RR. 2015. Characterisation of the chemical profiles of Brazilian and Andean morphotypes belonging to the Anastrepha fraterculus complex (Diptera, Tephritidae). In De Meyer M, Clarke AR, Vera MT, Hendrichs J (Eds) Resolution of Cryptic Species Complexes of Tephritid Pests to Enhance SIT Application and Facilitate International Trade. ZooKeys 540: 193-209.

- Vera MT, Cáceres C, Wornoayporn V, Islam A, Robinson AS, De La Vega MH, Hendrichs J, Cayol JP. 2006. Mating incompatibility among populations of the South American fruit fly Anastrepha fraterculus (Diptera: Tephritidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99: 387-397.

- Zucchi RA (2016) Fruit flies in Brazil – Anastrepha species their host plants and parasitoids. http://www.lea.esalq.usp.br/anastrepha (30 November 2017)